Published the 06/06/2019

– David Leconte, Université Rennes, CHU Rennes, Pôle Anesthésie-Samu-Urgences-Réanimations, F-35033 Rennes, France ;

– Hélène Beloeil, Université Rennes, INSERM, INRA, CIC 1414, Numecan, CHU Rennes, Pôle Anesthésie-Samu-Urgences-Réanimations, 2 Rue Henri Le Guilloux, 35033 Rennes Cedex 9, France ;

– Thierry Dreano, CHU Rennes, Service d’orthopédie et de traumatologie, F-35033 Rennes, France ;

– Claude Ecoffey, Université Rennes, CHU Rennes, CIC 1414, Pôle Anesthésie-Samu-Urgences-Réanimations, F-35033 Rennes, France

Abstract

Ambulatory surgery has grown to be the most common procedure in developed countries. Efficient quality of care and safety often require calling patient at day one after outpatient surgery to check patient’s recovery and search for complications. This increasing flow in same day surgery centres motivates the use of automatic systems to contact patients. The overall objective of this study was to evaluate automated software sending text messages (TM) to patients at day 1 after ambulatory surgery compared to classical phone calls. This prospective study took place in Rennes Teaching Hospital, France, from June 1st, 2015 to December 15th, 2016. All patients owning a mobile phone were included, adults and children by means of their parents. The primary end point was the rate of successfully contacted patients, compared to usual phone calls in 2014. In cases of no response or an abnormal response, an automatic alert was sent to the ambulatory unit. Within the 7246 patients included, response rate to TM was significantly higher than response to phone calls in 2014 (87% vs 57%, respectively p < 0.0001). Most patients (85%) responded in less than 60 min. The TM algorithm detected 36% alerts (12% for lack of response to TM and 24% for TM’s content). The total of reached patients’ rate with TM and then phone call after an alert was 90%. Post ambulatory discharge follow-up using automated TM was successfully and easily experienced as more patients were contacted.

Introduction

Thanks to improvement in both surgical and anaesthetic techniques resulting in quicker recovery times, fewer complications, higher patient satisfaction, and reduced costs of care, ambulatory surgery is expanding throughout the world and future projections are now considering that at least 75%, if not more, of all procedures will ultimately be carried out in ambulatory surgery centres [1]. That is the reason why it has been put at the center of public health policies over the last decade [2]. Organisational issues are among the key factors that may enhance the development of ambulatory surgery and are major determinants for ensuring efficient quality of care and patient safety. Consequently, international scientific societies have defined practical recommendations on ambulatory surgery [3, 4]. Day surgery units must agree how support is to be provided for patients in the event of postoperative problems. Generally, it requires monitoring by calling each one of them at day one after surgery. It allows checking patient’s recovery and search for complications [5]. But with the increasing flow in same day surgery centres, it is consuming too much staff’s time. That time can be considered lost for patient’s care. For example, in France, the nationwide OPERA study undertaken by the French Society of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care (SFAR) to characterize the organizational processes of ambulatory surgery, revealed that an average of 15% of the patients are not called with numbers as high as 55% on Saturday mornings [6]. Calls are mostly made by nurses (70%), secretaries (5%) and physicians (1%). Therefore, it motivates the use of automatic systems to contact patients. Today, 93% of French population owns a mobile phone (almost 100% of students and active workers and 74% of people older than seventy years) and send text messages (TM) daily [7]. TM were already shown to benefit diabetes surveillance, treatment observance, smoking cessation or weight management alongside with high patient’s satisfaction [8–10]. In the ambulatory setting, Garnier et al. compared phone calls and TM reminders for the respect of preoperative instructions before surgery. The use of TM was associated with a significant improvement in compliance with the preoperative instructions [11]. The potential benefit of the use of TM instead of call at day one after outpatient surgery has not been yet studied in the medical literature. Therefore, we designed a study to evaluate and compare postoperative surveillance at day 1 after ambulatory surgery using automated text messages compared to phone calls. The objective was to show the feasibility in daily practice and the efficiency in reaching patients with TM.

Patients and methods

This prospective study took place in Rennes Teaching Hospital, France, from June 1st, 2015 to December 15th, 2016. All patients owning a mobile phone were included, adults and children by means of their parents. They were all given instructions before discharge by nurses about day 1 follow-up with TM. TM were sent automatically by Calmedica® Society, Paris. To ensure confidentiality, the Calmedica® web site (https:// www.memoquest.com) is protected and only the patients’ telephone number was entered online. The society did not access any personal medical information except for responses to TM. Prior to beginning the study and the use of TM, the TM sent to all patients at day 1 was designed by our medical team involving an anaesthesiologist and a surgeon (see appendix). Along the study, TM were modified twice to improve answer’s rates and decrease unnecessary alerts. The study was then divided in 3 periods of time (see appendix). The primary end point was the rate of successfully reached patients using automated TM compared to usual phone calls the year before (2014) in the same hospital. Further analyses included number of alerts, patient’s lack of response to TM, inappropriate answers (error in responding to the TM, i.e. TM answers including any word besides those asked), TM’s content alerts (predetermined medical alert: pain rated higher than 4 on a 10-point numerical rate scale (NRS), emergency room consultation since hospital discharge, temperature above 38 °C, nausea, vomiting, bleeding; and false alert, i.e. part of inappropriate answer when patient did not need to be called). We also recorded delay for TM response. All TM responses during the study period were analysed. For statistics comparison of 2 groups, we used Student’s parametric T test or non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. As for comparison of responses’ rates, we used parametric test of chi-squared or non-parametric Fischer test. Statistical significance was set as p < 0.05. All analyses were realized with the SAS 9.4® program. Results are expressed as mean ± SD

Results

Population

At the end of the study 7818 patients were prospectively included. Unfortunately 572 patients were lost to follow-up due to a mismatch between Calmedica® files and hospital files’. The phone numbers of these patients were not available. The final number of patients was 7246 with a median age of 37 [0–95] years.

Responses

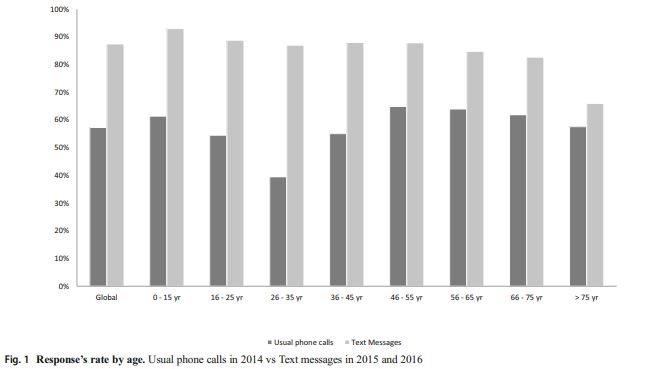

Global response rate to automated TM was 87% (n = 6343/7246). From 78% (n = 439/559) during the first period it significantly increased to 91% (n = 4733/5225) during the third period (p < 0.0001). Women (compared to men) and minor patients (compared to adults) had a better response rate (respectively p = 0.003 and p < 0.001). Analysis by age showed that response rate dropped over 75 years (66%) (Fig. 1). TM response time was less than 10 min for 54% of patients and less than 60 min for 85% of them. Patients who were hospitalised at least twice in outpatient unit during the study (586 patients) did not have a significantly better response rate (83% for first hospitalisation and 87% for second or more; p = 0.116).

Comparison to usual phone calls

In 2014, 8317 patients with a mean age of 35 ± 25 years were hospitalised in the same day surgery unit in Rennes. Response rate for phone calls during the year 2014 was 57% (n = 4767/8317) and significantly lower when compare with TM (p < 0.0001). However, 21% of the patients were not called in 2014. A total of 2195 (26% of patients) messages were left on the answering machine and only 424 of them (19%) called back the unit. Analysis of response rate by age showed that 26–35 years old were the least responders (39% of success rate). Patients older than 75 years were more likely to answer the phone (58%) (Fig. 1).

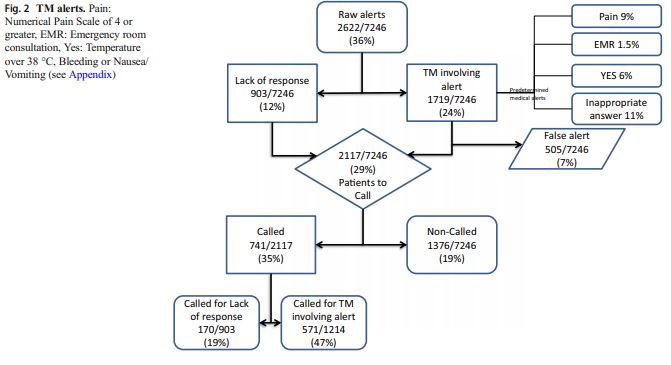

Analysis of the alerts

Repartition and causes of alerts along the study are detailed Fig. 2. Throughout the 3 periods of the study the proportion of alerts decreased. Concerning raw rate of alert, from 48% in period 1 it significantly decreased to 32% during the third period (p < 0.0001). It was the same for patient’s lack of response to TM (21% in period 1 and 9% in period 3 (p < 0.0001)), and TM’s involving alerts with 27% in period 1 and 22% in period 3 (p = 0.0008). The number of inappropriate answer (n = 805, 11%) and false alert (n = 505, 7%) were stable during the study. Likewise, the proportion of patients needing to be called dropped from 42% in the first period to 25% in the third period

(p < 0.0001). On the other hand, the proportion of patients needing a call and actually called increased from 24% to 43% in third period (p < 0.0001), both thanks to the growth of calls for TM content (from a portion of 33% in first period to 56%) and for lack of response (from 16% to 22%). This allowed the proportion of non-called patients who should have been, to drop from 32% to 14% in the third period (p < 0.0001). A certain amount of calls (n = 313/7246, 4%) were made without any valid reason. Finally, as 170 (2%) patients who did not answer to automated TM were successfully reached by phone, it brings the total of reached patients’ rate with TM and then call to 90% (n = 6513) along the study. Only 10% (733/7246) of the patients were never reached.

Discussion

This study showed that postoperative surveillance at day 1 after ambulatory surgery using automated TM is feasible and more efficient than usual phone calls. Indeed, phone calls are not really efficient for many reasons: a high proportion of patients does not answer the hospital call and they do not call back after a message. As shown in our study, it is especially true for young adults. Another reason is that phone calls are time consuming for staff nurses. Before the implementation of automated TM in our unit all patients were never called because of a lack of nurse time. As reported by the OPERA study [6], it was especially true when nurse staff was reduced during holidays or weekends, with 55% of patients never called on Saturday. After implementation of automated TM in our study, phone calls to patients whose TM’s answer triggered an alert (which could be a medical alert) were prioritized over calls to patients who did not respond to the TM. Moreover, TM allowed a really high answer rate, in a relatively short period of time and answers can easily be, automatically interpreted by an algorithm included in the software. TM efficiency improved during the study: lack of response decreased drastically when a last TM was automatically added 65 min after the first one in case of lack of answer. Mandatory phone calls after a TM alert dropped in our study. They were roughly divided by 4. It allowed the proportion of non-called patients to also drop because less human resources were needed. Indeed, one phone call is estimated to last 5 to 7 min. All these minutes saved from phone calls could be reinvested into patients’ care. It is also probably cost effective. However, we did not analyse the potential financial benefit of the automatic TM system vs phone calls. When analysing response rates according to the age of the patient, the differences observed with phone calls (i.e. younger patients not answering phone calls when compare with older patients) disappeared with TM. One could have hypothesized that elderly patients would be more reluctant to answer TM but it was not the case in our study. Patients of all ages were more likely to answer to TM than to phone calls. TM’s content alerts analyses showed low rates of complications. These results are in accordance with the literature on the safety of outpatient postoperative course [12,13]. The incidence of complications has dropped in the last 20 years. Indeed, Chung et al. reported that more than 25% of the patients called 24 h after the surgery experienced pain while we reported only 9% [14]. Carrier et al., in their study, already showed the feasibility of home surveillance by TM after colorectal surgery and highlighted the great satisfaction of patients [15]. More recently Anthony et al. successfully collected pain information over a full week after hand surgery through automated TM [16]. In the same way, use of Mobile App improved follow-up and link with the patient in ambulatory surgery [17]. Altogether these findings highlight the benefits of the use of technology to communicate with patients. Moreover, the steadiness of the inappropriate answer’s ate during the study period and the fact that patients who came twice did not have a better response rate let us hypothesize that learning how to use the algorithm is intuitive for both patients and nurses; making the system easy to implement and generalize in other hospitals or units. The main limitations of this study are: 1) selection bias, patients without a mobile phone could not be included, especially elderly patients. However, as recommended for outpatient surgery, patients are not alone the night after surgery [4]. The relative accompanying the patient is often younger and owns a mobile phone; 2) the lost to follow-up patient’s proportion is not as low as we would have expected with TM. The main reason for lost to follow-up was an administrative mismatch and we could hypothesize that their distribution is homogeneous.

Conclusion

Post ambulatory discharge follow-up using automated TM was successfully and easily experienced as more patients were contacted. This method of surveillance can be considered as a safe and efficient alternative to the nurse phone calls. Items about surgical outcomes could be added to further improve patient’s care.

Acknowledgements : The authors thank Calmedica, Estelle Le Pabic (statistician), Hélène Gilardi, Véronique Joyeux and Laurence Labarrere

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest:The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Appendix

The digital platform from Memoquest was programmed to automatically send text messages to patients the day after their ambulatory surgery. In the morning between 9:00 am and 10:00 am, they received a series of questions (see below) and were asked to answer it. Then, everyday around 12:00 pm, an automatic email was send to the nurse team by the digital platform. The email contained all patients’ phone number that triggered a predetermined alert as detailed below:

-first period: TM answers with TEM,NV,BLE, EMR or a number of four or higher

-2nd and 3rd periods: TM answers with YES, EMR or a number of four or higher

-TM answers including other words than those asked in TM

-Lack of response to TM

TM content, 1st version

The morning after the surgery, all patients received the following TM:

-If your temperature is higher than 38 °C, just answer the 3 letters TEM

-If you had nausea or vomiting since your return to home, just answer the 2 letters NV

-If you had any bleeding, just answer the 3 letters BLE

-If you had trouble sleeping, just answer the 3 letters SLE

-If you called the hospital or if you came to emergency room during the night, just answer EMR

-If you do not have any symptom, just answer the 2 letters NO

-If you had any pain since your return to home, give your maximum level of pain with a number between 0 and 10.

If the number was higher than 3, patient received the next TM:

-What’s your actual level of pain? Answer with a number from 0 to 10.

TM content, 2nd et 3rd version

2nd version

The morning after the surgery, all patients received the following TM:

-Rennes Hospital: Concerning the follow-up of your intervention, if everything is alright, just answer the 3 letters EIA.

-If your temperature is higher than 38 °C, or if you had nausea or vomiting or bleeding, answer YES to this text message.

-If you had trouble sleeping, just answer the 3 letters SLE

-If you called the hospital or if you came to emergency room during the night, just answer EMR

-If you had any pain since your return to home, give your maximum level of pain with a number between 0 and 10

If the number was higher than 3, patient received the next TM:

-If you already took the painkiller prescribed give your actual level of pain with a number between 0 and 10.

-If you did not take the painkiller prescribed, take it now and give your level of pain in 45 min with a number between 0 and 10.

3rd version

Same content than 2nd version added to: If the patient did not answer the questions after 65 min, patient received this last TM:

-Rennes Hospital: You did not answer back any TM, answer now or if everything is alright, answer EIA.

Pediatric vision

The morning after the surgery, all patients received the following TM:

-Rennes Hospital: Concerning the follow-up of your child’s intervention, if everything is alright, just answer the 3 letters EIA.

-Rennes Hospital: If your child’s temperature is higher than 38 °C, or if he had nausea or vomiting or bleeding, answer YES to this text message.

-Rennes Hospital: If your child had trouble sleeping, just answer the 3 letters SLE

-Rennes Hospital: If you called the hospital or if you came to emergency room during the night for your child, just answer EMR

-Rennes Hospital: If your child had any pain since your return to home, give his maximum level of pain with a number between 0 and 10. If the number was higher than 3, patient received the next TM:

-If you already gave to your child the painkiller prescribed, indicate his actual level of pain with a number from 0 to 10.

-If you did not give the painkiller prescribed, give it to him now and indicate his level of pain in 45 min with a number from 0 to 10.

If the patient did not answer the questions after 65 min, patient received this last TM

-Rennes Hospital: You did not answer back any TM, answer now or if everything is alright, answer EIA.

Once alerted, nurses called the patients and asked for more details and then referred to the responsible surgeon if needed. If the trigger was an absence of answer, nurses called the patient like they used to do it before automatic TM implementation.

Note: The study was divided into 3 periods of time corresponding to the date of TM modification: 1) beginning of the study to the second of September 2nd, 2015, 2) 09/02/2015 to 02/11/2016 and extension to all ambulatory units of Rennes Teaching Hospital from the 01/07/2016 to 01/22/2016, and 3) last modification of TM from 01/22/2016 or 02/11/2016 depending of the unit to the end.

References

1. Toftgaard, C., Day surgery development and the role of international association for ambulatory surgery. J Exp Med Surg Res 16:166 – 169, 2009.

2. Fosnot, C., Fleisher, L., and Keogh, J., Providing value in ambulatory anesthesia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 28:617 – 622, 2015.

3. Maciejewski, D., Guidelines for system and anaesthesia organisation in short stay surgery. Anaesthesiology Intensive Therapy 45:190 – 199, 2013.

4. Verma, R., Alladi, R., Jackson, I., Johnston, I., Kumar, C., Page, R. et al., Day case and short stay surgery: 2. Anaesthesia 66:417 – 434, 2011.

5. Hwa, K., and Wren, S. M., Telehealth follow-up in lieu of postoperative clinic visit for ambulatory. JAMA Surg 148:823 – 827, 2013.

6. Beaussier, M., Albaladejo, P., Sciard, D., Jouffroy, L., Benhamou, D., Ecoffey, C. et al., Operation and organisation of ambulatory surgery in France. Results of a nationwide survey; the OPERA study. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 36:353 – 357, 2017.

7. Research Center for Study and Observation of Living Conditions (Centre de Recherche pour l’Etude et l’Observation des Conditions de vie, CREDOC). La diffusion des technologies de l’information et de la communication dans la société française 2014.

8. Bassam Bin, A., Al Fares, A., Jabbari, M., El Dali, A., and Al Orifi, F., Effect of mobile phone short text messages on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Int J Endocrinol Metab 13:e18791, 2015.

9. Reid, M., Dhar, S., Cary, M., Liang, P., Thompson, J., Gabaitiri, L. et al., Opinions and attitudes of participants in a randomized controlled trial examining the efficacy of SMS reminders to enhance antiretroviral adherence: A cross-sectional survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 65:e86 – e88, 2014.

10. Leigh Rathbone, A., and Prescott, J., The use of Mobile apps and SMS messaging as physical and mental health interventions: Systematic review. J Med Internet Res 19:e295, 2017.

11. Garnier, F., Sciard, D., Marchand-Maillet, F., Theissen, A., Mohamed, D., Alberti, C. et al., Clinical interest and economic impact of preoperative SMS reminders before ambulatory surgery: A propensity score analysis. J Med Syst 42:150, 2018.

12. Fleisher, L., Reuven Pasternak, L., Herbert, R., and Anderson, G., Inpatient hospital admission and death after outpatient surgery in elderly patients. Arch Surg 139:67 – 72, 2004.

13. Chung, F., Mezei, G., and Tong, D., Adverse events in ambulatory surgery. A comparison between elderly and younger patients. Can J Anaesth 46:309 – 321, 1999.

14. Chung, F., and Mezei, G., Adverse outcomes in ambulatory anesthesia. Can J Anesth 46:R18 – R26, 1999.

15. Carrier, G., Cotte, E., Beyer-Berjot, L., Faucheron, J. L., Joris, J., and Slim, K., Post-discharge follow-up using text messaging within an enhanced recovery program after colorectal surgery. J Visc Surg 153:249 – 252, 2016.

16. Anthony, C., Lawler, E., Ward, C., Lin, I., and Shah, A., Use of an Automated Mobile Phone Messaging Robot in Postoperative Patient Monitoring. Telemedicine and e-Health 24:61 – 66, 2018.

17. Armstrong, K. A., Coyte, P. C., Brown, M., Beber, B., and Semple, J. L., Effect of home monitoring via Mobile app on the number of in-person visits following ambulatory surgery: A randomized clinical trial.JAMA Surg 152:622 – 627, 2017

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations